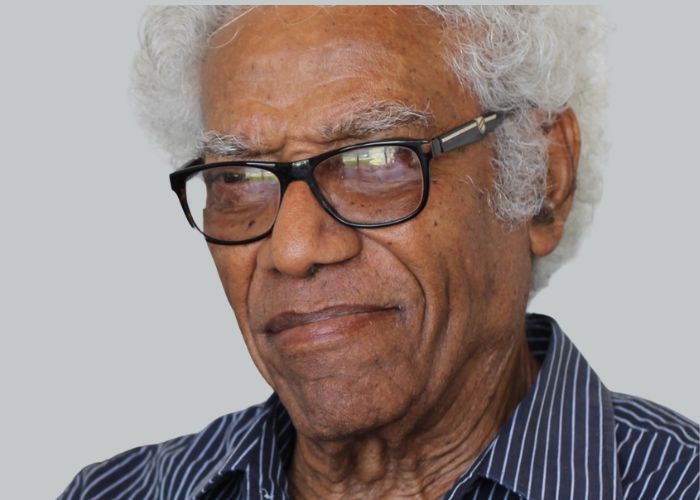

George Lamming is an Inviolable Legacy of Afro-Caribbean Literature

Celebrating a Pan African literary figure and his intellectual and socio-cultural impact on global Africa

Introduction

It is in African tradition to talk good of one when he is dead, but not to talk about him or her when he or she is still alive. I don’t know why this heritage has persisted. I am very sorry about this, especially when I have only chosen to write about George Lamming when he is dead even though I have had three decades of savouring the juice from his literary talent for over three decades when he was still alive and kicking in the Caribbean Islands and even Africa, especially in Nairobi my home city. George Lamming, a novelist known for his book In the Castle of My Skin, died on Saturday, June 4, 2022, at the age of 94. He died in Barbados, his country of birth. Throughout his life, George Lamming was a towering black writer gifted with appealing literary and creative capability. He was as avuncular to Africa, African literature, and Political socialization as well as cultural freedom in Africa just as Langston Hughes, the Black American poet, playwright, and novelist of the Harlem Renaissance was. Lamming was Africa’s illustrious son in an intellectual and cultural sense, not only an African Caribbean from the Island Country of Barbados, but we in Africa, especially those of us who loved literature, treasured Lamming with our souls and blood not to mention spirit, as our son, brother and comrade.

But before I express my grief, my unwavering love for Lamming’s literary capability propels me to admire and salute his nine decades of a well-lived life, especially, when I travel down my literary memory lane by musing about his extraordinary literary prowess in the authorial excellence and artistic brio as well as his unique intellectual mettle displayed in his seminal book In the Castle of My Skin.

This book was the first work of prose which Lamming wrote in the middle of the last century when he was only at the age of twenty-three. Some kind of literary phenomenology which echoes George Lamming’s literary life as a phenomenon provokes any curious mind to ask; how did George Lamming manage to write ‘In the Castle of My Skin’, such a spell-binding book that is significantly a milestone in the history of black literature and Africana studies when he was only a big baby at the age of twenty-three? I looked for the answers in Rene Wellek’s Literary Theory, but still, I did not get a proper explanation.

Lamming: a challenge to today’s youths in Africa

My question is triggered by my personal experience in the world of liberal arts that I encountered through working for over ten years as a lecturer with a focus on social sciences in different Universities in Kenya. My special or particular encounter is that there is no Kenyan boy or girl at the age of twenty-three today who can write anything near in stamina to George Lamming’s In the Castle of My Skin. Yes, I am aware of some historical accidents in the East African literary scape where talents of the last century in the likes of Scholastica Mukasonga, Clemantine Wamariya, Jennifer Nasumbuga Makumbi and Oduor Okwir as well as some titans in the likes of Okot P’ Bitek, Shaban Bin Robert and Francis Imbuga that began to write and publish in their twenties, but still the literary eventuality of Lamming commands a superlative position in terms of talent, simplicity, with might of humor, communication of complex political challenges in accessible language and capacity to package local cultural experiences for universal or globalized consumption with easy and smoothness.

This is also a question that takes us back to reading Rene Wellek’s Literary Theory, especially the chapter on ‘Literature and Human Psychology’ in which Wellek makes some literary inquiry on whether a writer is born or educated. Wellek’s theory on literary psychology would force us to ask this;- was George Lamming a “borne writer” or an educated writer? Can a literature department in Africa or America of today manage to train a boy to write a novel that can compete with In the Castle of my Skin at the age of twenty-three?

This question also has some value in the use of synecdoche for cultural analysis. It is a microcosmic question with global intentions given that when you make conversations with those who have taken the time to study Caribbean literature you easily come to a well-supported conclusion that Africa and the Caribbean islands are the epicenters of black literature, both in a temporal sense and a geographical sense. Yes, Africa began seeing its native writers four or fewer centuries ago, starting with Olaudah Equiano to the current conditions of explosion in literary talents in Nigeria, Congo, Kenya, South Africa, Egypt, and Cameron. But still, the last two centuries of Caribbean Literature have had a comparative penchant impact on the study and practice of black literature as well as Africana culture. This is the perspective of synecdoche giving us a logic of extension emanating from the cultural eventuality of George Lamming justifiably generalizable to Caribbean islands and hence providing all logic to question the legacy of cultural miracles behind the literary excellences and paragonic literary civilization as testified through literary efforts by V. S. Naipaul, Derek Walkot, Sam Selvon, Kamau Brathewaite, Water Rodney, Frantz Fanon, and Afua Cooper.

Lamming’s intellectual and socio-cultural impact on the Caribbean and Africa

In the same stretch we the people in Africa, especially from East Africa, are also bound to think in terms of the current history of Africa’s social-economic relations with the Caribbean islands. We are bound not to avoid a philosophical position that, even though the death of George Lamming is untimely to most of us who loved him and his literary work, still it is not a moment of darkness. It is a true moment of an unflagging candle that shines on the truth about how George Lamming influenced and inspired intellectual growth among Africa’s social thinkers of the last century; just in the same measure as the Caribbean Islands have successfully influenced the formation of anti-colonial consciousness among African political leaderships. For example, George Padmore influenced Jomo Kenyatta and Kwame Nkrumah to give institutional thought to the need for Africa’s freedom from the tyranny of colonial shame. The same is the case for Walter Rodney when he was working as a lecturer and researcher in Tanzania during the mid-years of the last century. Walter Rodney shaped the intellectual growth of the young scholars who went on to become significant pillars of African politics and scholarship. Their list is great, ranging from Yoweri Museveni, Sally Kosgei, John Garang, and Austin Bukenya to Dr. Amukowa Anangwe. Walter Rodney shaped the destiny of their intellectual journey when they were students at the University of Dar es Salam.

Beyond academics and classroom activities, Walter Rodney was also a public revolutionary thinker who challenged the ever-dissembling Julius Nyerere to improve the quality of thought in the kind of socialism practiced in Tanzania at that time. And also, no university and any other institution of higher learning in Africa today can forget to appreciate the kind of cultural and intellectual benefit Africa has enjoyed from How Europe Underdeveloped Africa and also, the history and Human statistics of Trans-Atlantic Slavery, two very important books by Walter Rodney. This is the same accolade that we extend to Derek Walkot, Frantz Fanon, and Aime Ceasaire for the respective social-cultural influences they had on Africa. Kenya, in particular, has benefited greatly from several Caribbean intellectuals and professionals, especially when we remember that Kamau Braithawaite was an intellectual missionary at the University of Nairobi in 1975, Kenya’s first chief Justice was a Caribbean native, Frantz Fanon had some short stay in Nairobi, and more currently, Bob Collymore from Guyana contributed his prowess in corporate leadership to strengthen corporate excellence at Safaricom, a mega corporation in Kenya.

I know my adult readers from Kenya will always want someone to mention to them how George Lamming influenced Ngugi wa Thiong’o. To me, this is not enough until I mention that George Lamming’s book In the Castle of My Skin is a source of literary influence to very many Kenyans beyond Ngugi wa Thiong’o. Personally, I read this book in 1988. By then it was a set-book for literature students sitting for form five and form six literature examinations. I was not an A’ level student, I was in my upper primary of schooling, but I came from a village that was flooded with A ‘level literature students and hence it was not difficult for me to encounter spillovers from the pages of George Lamming’s In the Castle of my Skin.

The kind of excitement and adolescent hyper that these A ‘level students displayed when talking publicly about the characters in Lamming’s book In the Castle of My Skin catapulted me to defy the pathetic state of wanting intellect in my level of education to read the book. Above all else and against all odds, I enjoyed the book. I loved and hated the characters in the book. I loved the school boys with passion, but also, I hated the landlord and the school headmaster with passion. I loved the boys for their swiveling boyishness, but I hated the landlord for disturbing the birthday party at the house of a poor tenant. At most, I hated the sugar cane plantation and its system of labour, just the same way I hated the school headmaster for showing ruthless expertise in how to flog until shredding the buttocks of unruly school boys.

Since then, I have been reading Lamming’s In the Castle of My Skin every year in June. I read it in June because June is the month of Caribbean literature. In the year 2022, I had chosen that my June reading list would be James Marlon’s Book of the Night Women and Lamming’s In the Castle of my Skin. I usually read two books at once, hence I had read these two books halfway. Unfortunately, on 6th June, I got an email from James Murua’s Literary blog that George Lamming is dead.

More saddening was that I have not heard any Kenyan media, young people, and even members of the academic community talking about the sad passing on of George Lamming. I am sure they were not aware of him; this is so given that the current intellectual culture in Kenya is focused on identity and politics, money-making, buying an urban plot, and owning a laptop for developing commercial tendering proposals. It is not easy to come by a Kenyan youth of today displaying admirable depth of intellectual curiosity. I don’t know who to blame.

Lamming’s Education and Literary Works

Ergo, it is out of this perspective that I want to inform my young readers from Kenya that George Lamming was born in Carrington Village in Barbados, on June 8, 1927. He went to Roebuck Boys’ School. After that, he won a scholarship to Combermere School. This is where he met his teacher, Frank Collymore. Frank Collymore was a man of the arts and also a publisher of the literary journal known as BIM. It is Frank Collymore who inspired Lamming with a passion for reading and writing poetry. Then, Lamming went to Trinidad in 1946. He worked there as a school teacher for four years at a school known as El Collegio de Venezuela in Port of Spain before moving to England to work in a factory for a short time before he became a broadcaster for the BBC Colonial Service.

George Lamming entered the world of serious academia in 1967 as a writer-in-residence and lecturer at the Creative Arts Centre and Department of Education at the University of the West Indies. After this, he served as a visiting professor and writer-in-residence at the City University of New York. Alongside this, he was also a faculty member and lecturer at the University of Texas at Austin and the University of Pennsylvania, a distinguished visiting professor at Duke University, a visiting professor of Africana Studies and Literary Arts at Brown University, and a lecturer at Universities in Tanzania, Denmark, and Australia.

Lamming wrote a total of six novels and four non-fiction books. I name a few: The Emigrants (1954), Of Age and Innocence (1958), Season of Adventure (1960), and Water with Berries (1971) as well as a collection of essays under the title The Pleasures of Exile. Maybe this life of struggle and hard work is the reason why George Lamming was able to write In the Castle of My Skin at the age of twenty-three.

Alexander Opicho is a Poet, Short Story Writer, Essayist, Playwright, Culture Critic, and Corporate Trainer from RCMRD, Nairobi, Kenya.